Objects that interested me in the Food Museum collection

Anahita Harding reflects on her time as Curatorial Fellow at the Food Museum – part of the Curating Visibility programme Curating Visibility – Screen South.

Read about Anahita’s experience in her previous blog post here Exploring Accessible Cooking Tools – Food Museum

“While planning objects to go into the Food not Cuts exhibition (Food Not Cuts – Food Museum), there were a couple of objects which caught my eye. I didn’t include them in the end, as they didn’t directly relate to the relationship between food, cooking and disability but I’d like to share them with you here:

Metal Junk Sculpture – Person with Heart-Shaped Head (1960–1979)

Redvers Taylor (1900–1975)

Object number: STMEA:2001-34.4c

As I looked through the sculptures by Redvers Taylor, I was struck again by how much I love his sculptures. They reveal such a deep connection between human form and industrial tools.

Taylor’s work fascinates me – I’m not a sculptor myself, but as an artist I’m interested in the body, and in how disabled people are represented. One sculpture in the collection was previously labelled “the Crippled Figure” – a title that immediately caught my attention. The name has since been updated but encountering that word in the collection was surprising.

The term “crippled” is now considered outdated and offensive. It’s been used against me before, and I know how loaded it can feel. Whether or not it was the artist’s original title is unclear – names of artworks often shift over time or can be applied by others when no title exists. It pushed me to look closer.

The sculpture itself is bulky and heavy. It has a hollow, heart-shaped head, narrowing into a trunk. Two iron-bar legs extend downward, drilled with machine holes, while the arms hang down (one ending in a cylinder, the other flat).

Taylor saw human forms in abandoned fragments of agricultural machinery, gathering them to create his sculptural characters. Before entering the museum’s collection, these works lived in a friend’s house and garden, where visitors enjoyed them informally.

Art critics have sometimes dismissed this style of sculpture, calling it “junk” art. In my opinion, Taylor gave life to figures that feel both fragile and powerful.

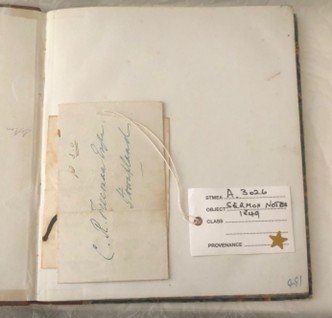

Notebook Containing Sermons (1845–1849)

Object number: STMEA:A.3026

While looking through the archives, I found a small notebook that intrigued me. It didn’t fit within Food not Cuts, but it’s a story worth sharing.

Inside the notebook are neatly handwritten sermons, recorded by a vicar for one of his parishioners, C. R. Freeman, who was deaf. In mid-19th-century Suffolk, church would not have been just for religious purposes but also functioned as a social space. By writing out his sermons, the vicar made sure that Freeman could take part in the life of the parish.

The notebook contains sermons from Stowupland Church between 1845 and 1849, with some long gaps between entries. One sermon was written for a funeral. Alongside the text, there are two loose sheets: an invitation for Rev. Smith to dine at Stowupland Hall every Sunday, and a scrap of paper with doodles, and even a game of hangman.

I really enjoyed looking through this notebook, as it has a story of accessibility and inclusion.”

The Food Not Cuts exhibition is on until 9 November in Abbots Hall Dining Room

Share this article